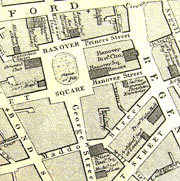

The history of the parish at St George's Hanover Sqaure in the City of Westminster

1862 Cassell Weekly Despatch map

The new parish consisted of the two Out Wards of the Parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields lying to the west of the City of Westminster. The first perambulation of its boundaries took place on Thursday, May 14th, 1725, being Ascension Day. A party of Vestrymen and parishioners met in Swallow (now Regent) Street, making their way north to Oxford Street, along which they proceeded westwards to the Tyburn Road as far as the head of "the Ponds", now known as the Serpentine. Their course then took them down the eastern edge of the ponds as far as Knights Bridge, where they were met by the Rector and Churchwardens. After prayers in the Knightsbridge Chapel they set off southwards along the course of the West Bourne to the River Thames, then eastwards for three quarter of a mile, when they turned northwards to Buckingham House and Piccadilly, and then by a devious route by Green Park and St James's Street back to Swallow Street. Boundary marks were placed at regular intervals, including one on the wall of Buckingham House. They had walked eight and a half miles round an area of just over 993 acres.

The lands encompassed consisted mainly of the ancient Manor of Eia, mentioned in the Domesday Survey of 1086 as being held by Geoffrey de Manville, one of William the Conqueror's noblemen. Geoffrey later gave the manor to Westminster Abbey , which owned it till 1536, when it became Crown property. Henry VIII retained Hyde Park for hunting ground. The remainder of the Manor, consisting of the Manor of Ebury and the Bailiwick of Neate, was leased to private persons. In 1623 James I sold the freehold, which subsequently was acquired by Hugh Audley, a wealthy speculator. The estate descended through Hugh's sister Elizabeth to his great-grandniece Mary Davies, who in 1677 married Sir Thomas Grosvenor, a rich Cheshire baronet, from whom are descended the Dukes of Westminster.

Such was the area which the new Select Vestry had powers of administration. There were a hundred and one Vestrymen. Among them were seven dukes, fourteen earls, seven barons, and twenty-six other persons of title. They were responsible not only for the Church's affairs, but also for the civil government of the Parish; and the Vestry Minute books (now in Westminster City Archives) are a rich mixture of the ecclesiastical and the secular, and much time is spent on street lighting, highways maintenance, refuse disposal, the appointment of constables, beadles and nightwatchmen, and the levying of rates to pay for these services. There was also the supervision of the Workhouse in Mount Street, situated on the edge of the Parish Burial Ground. The Vestry assumed almost the status of a municipal corporation, and was presided over by the Rector and Churchwardens. Each Churchwarden held office for two years.

The parish: 18th century

The 18th century Rectors were intermittently resident, being Pluralists and holding other appointments elsewhere as Bishops or Deans, in spite of the fact that the living was considered a rich one, being worth about £1500 a year with a fine house in Grosvenor Street. The emoluments were sufficiently attractive for Dr. William Dodd, a Royal chaplain and popular preacher in 1774 to offer the Lord Chancellor's wife £3000 and an annuity of £500 to obtain the living for him. She reported the matter, he lost his reputation and was hanged three years later at Tyburn for forgery.

The Vestrymen faced grave problems through the growth of population. In the small streets and lanes behind the fine houses there was poverty and overcrowding. Drunkenness and disease were rife. Infant mortality was alarming. Between 1750 and 1755, of 288 children born in, or received into the Workhouse 137 died. Those who survived were put out to nurse or brought up in the institution, There education was minimal, and at the age of twelve or thereabouts they were bound apprentice to cotton mills or to the poorer sort of artisan. By 1762 the burial ground was full, and a new one was bought in the Bayswater Road. By 1785 the Workhouse itself was no longer adequate, and an additional house was bought in Chelsea. Further burdens fell on the Vestrymen with the development of the land south of Hyde Park. A few streets were built between 1805 and 1810, and then the planned growth of Belgravia began in 1825. South of this, Pimlico was an area of market gardens and cow pastures until 1835 when they too began to disappear under the fine streets and houses laid out by the Grosvenor Estate. New parishes were carved out of the old, but the Vestrymen continued to be responsible for them. Only the ecclesiastical boundaries shrank to what they are today.

Although in the 18th century there were seven proprietary Chapels within half a mile of St George's, all well attended, there was little social conscience, but early in the 19th century, under the influence of the Evangelical Movement, churchpeople began to feel concern for the condition of the poor. A Parish School was established in 1804 by public subscription. In 1842 Lord Harrowby headed an investigation into local slums. A house-to-house visitation took place and found that 1,468 families of the labouring classes had only 2,147 rooms between them. The result was the establishment of the St George's Workmen's Model Dwellings Association in 1849, under the presidency of the Marquis of Westminster who provided necessary land for St George's Buildings in Bourdon Street.

The day of the pluralist Rector ended with the appointment of the Rev. Henry Howarth in 1845. He revolutionised Church and Parish, instituting weekly Communions and week-day services, and organised Sunday Schools which gave a general, not specifically religious, education. To these he added a Dispensary and Parish Nurse, a Dinner Kitchen, a Lending Library, and a second block of flats (Grosvenor Buildings). His successor, Edward Capel Cure, continued the work , complaining in 1878 that there was no social centre. The Duke of Westminster offered a site in Bourdon street, on which he paid for the building of a church (St Mary's), since St George's was not large enough.

The parish: 19th century and ahead

The Vestry noted that "for nine months of the year we have scarcely any residents of the upper classes", and concentrated on the building of an Institute, which opened in 1884 and included further dwellings (Bourdon Buildings), a Dispensary, a large hall, Working Men's Club, Youth Club, Gymnasium, Library, Kitchen and Restaurant, and Committee Rooms. Finally another large block of flats was erected in 1889 in North Row. Thus the Parish provided voluntarily what would nowadays be regarded as the State's responsibility. The Institute continued many of its social activities until after the 1939-1945 War, but with the decline of population, the termination of its lease, and the fact that most of its functions had been assumed by the Welfare state, it was closed in 1962, and demolished. The Model Dwellings Association still continues.

In the later 19th century the powers of the Vestry began to dwindle, and under the Local Government Act of 1889 it was finally abolished in the setting up of Westminster City Council in November 1900. It had done 175 years of useful work.The Old "Civil Parish" has gone, except in the administration of certain charities, but the Ecclesiastical Parish is still very much alive.